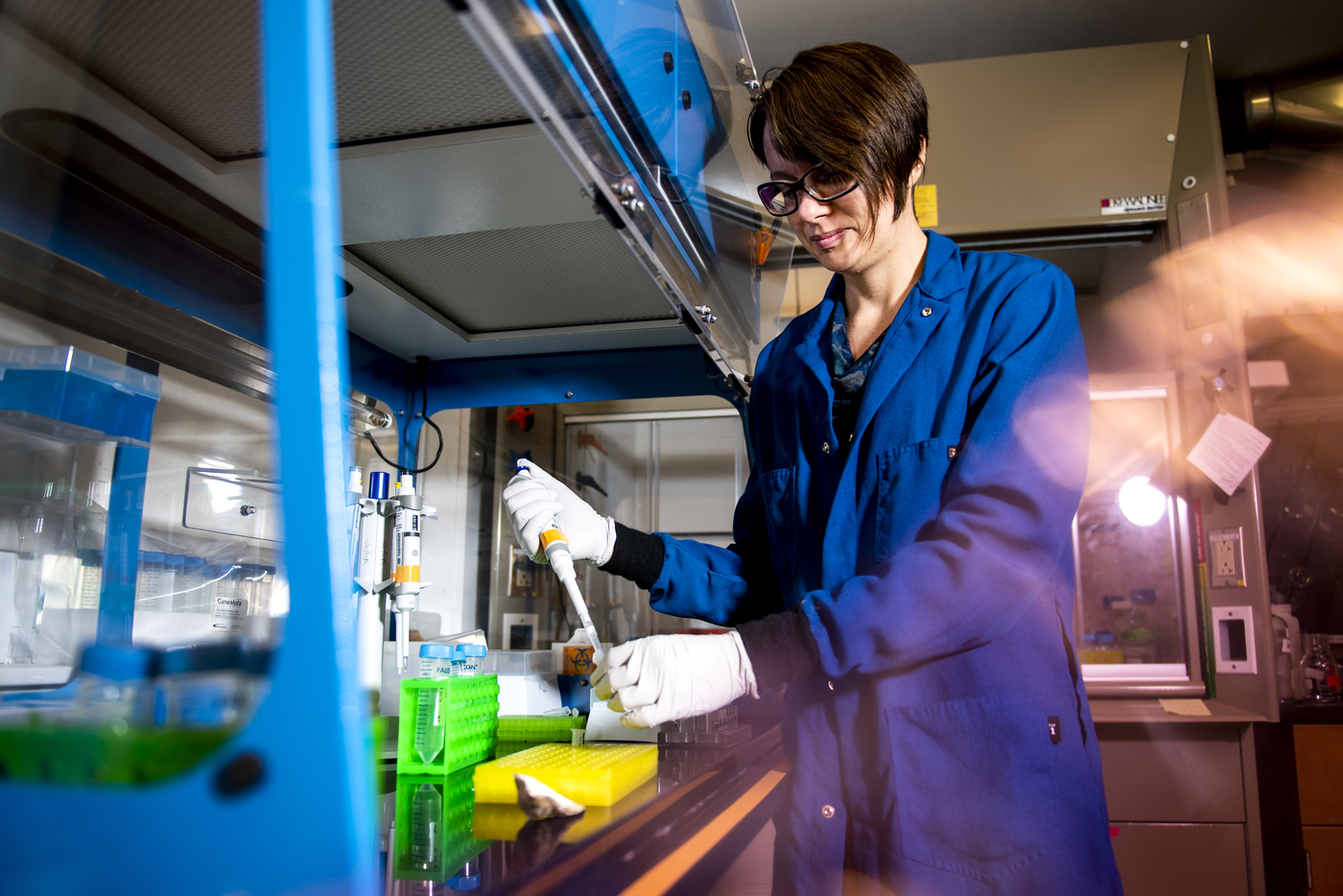

Katie Lotterhos is helping breed better oysters. Not just ones that taste better (although, that’s part of it), but importantly, ones that will be better suited to stave off disease and survive in warmer, saltier, and more acidic waters.

She, along with her colleagues, are doing it by searching for minuscule variations in the genetic makeup of certain oysters then using computer models to predict how those differences will help or hinder the bivalves in complex, changing environments.

“We can breed oysters that will be more resistant to disease, but how will they react to other stressors in their environments? There’s a need to understand how genomes affect how an organism performs against a number of variables,” says Lotterhos, associate professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern.

Her work has wide-ranging consequences, and not just for fans of the half shell.

As the planet’s oceans warm and become more acidic, aquatic species are racing to keep up. Some populations are migrating to new waters, adapting to new food sources, or simply dying off.

But humans may be able to help restore marine populations by moving them to more suitable environments or breeding for traits that enable them to survive on their own.