Think you’re safe from ticks in the city? Think again.

Thanks to increasing urban and suburban sprawl, forests are being parceled into smaller pockets of vegetation. Parks and backyards in the suburbs are now the perfect size to sustain mice, but not quite large enough to sustain foxes. That means mice can run rampant with no natural predators to keep their population at bay. And with mice, come ticks.

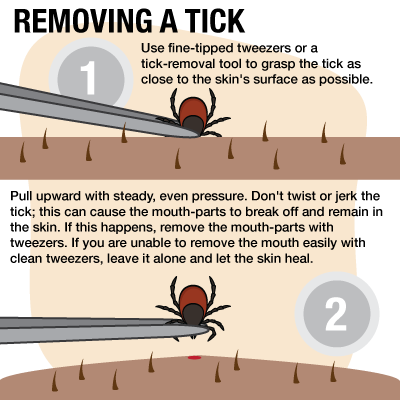

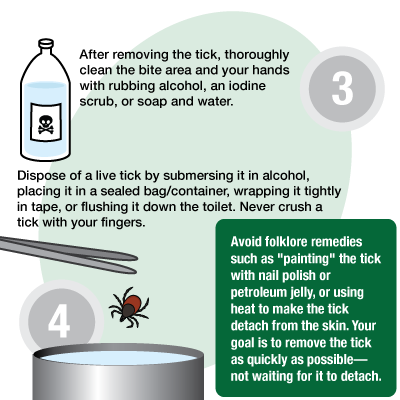

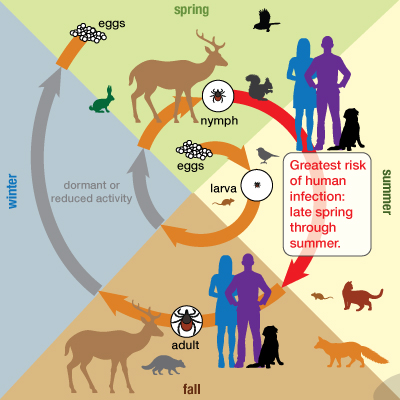

source: CDC

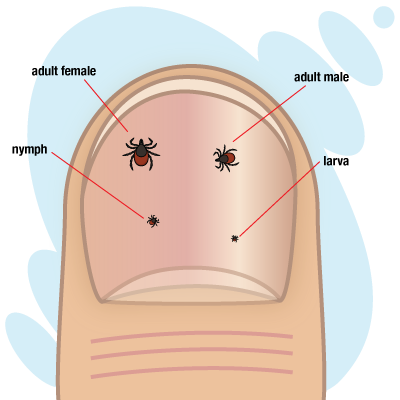

Mosquito, flea, and tick-borne illnesses in the United States tripled from 2004 to 2016, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blacklegged ticks, also known as deer ticks, carry at least five different illnesses, including Lyme disease.

While ticks can crawl slowly, their main mode of transport is hitchhiking, Lewis said. Ticks will gladly take a lift from deer, dogs, and people. But their primary host is the white-footed mouse, which is common in the New England forests, towns, yards, and cities, and is the primary transmitter of Lyme disease.

source: CDC

How serious is the illness? Lewis said it depends, since Lyme disease comes in two “flavors.” One is the acute disease: you get bitten by a tick, the pathogen causes a rash around the bite that looks like a bullseye, and you experience mild flu-like symptoms. As long as you are treated with antibiotics within a few days, the disease will go away.

But for about 10-20 percent of people, the antibiotic doesn’t work. These patients develop post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, also known as chronic Lyme.

“People get joint pain, muscle pain, fatigue, insomnia, a whole slew of symptoms,” Lewis said. “It can be a really debilitating condition.”

source: CDC

One of the problems with treating Lyme disease is that doctors prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic that was originally developed to treat other infectious diseases, such as staph or E. coli. These powerful antibiotics are unfriendly to the human gut microbiome—the symbiotic bacteria that affect the immune system. Lewis said he suspects that chronic Lyme disease is partly caused by these antibiotics wrecking the microbiome, while Borrelia burgdorferi is simultaneously destroying the immune system.

source: CDC

Until then, use an insect repellant containing DEET, shower after walks in the woods, and follow other tips for avoiding ticks—and don’t assume you’re immune in the city.