Our brains consist of different regions that support the cognitive functions we need to survive. But none of these regions work alone. They receive and send input at all times, firing cells in other parts within the brain, and creating the patterns of synchronized activity behind our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Researchers are imaging these patterns to predict how symptoms of psychiatric disorders develop in teenagers. Their new prediction model offers an important tool to address anxiety and depression in the U.S.

In a recent study, which was a collaboration among Northeastern, the University of California at Berkeley, and Vanderbilt University, the researchers identified specific patterns of activity in the brains of children, and predicted how symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity progress.

“This is a whole new way of looking at the brain just by looking at temporal correlations,” says Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli, a professor of psychology at Northeastern and lead author of the study. “These networks of brain activity are extremely helpful in terms of neuro prediction.”

In the U.S., teens put anxiety and depression among their biggest concerns, according to a recent survey by the Pew Research Center. Data from the National Institute of Mental Health show that suicide is the second leading cause of deaths among teenagers. And a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics found that children and teenagers visits to U.S. emergency rooms for attempted suicide doubled from 2007 to 2015.

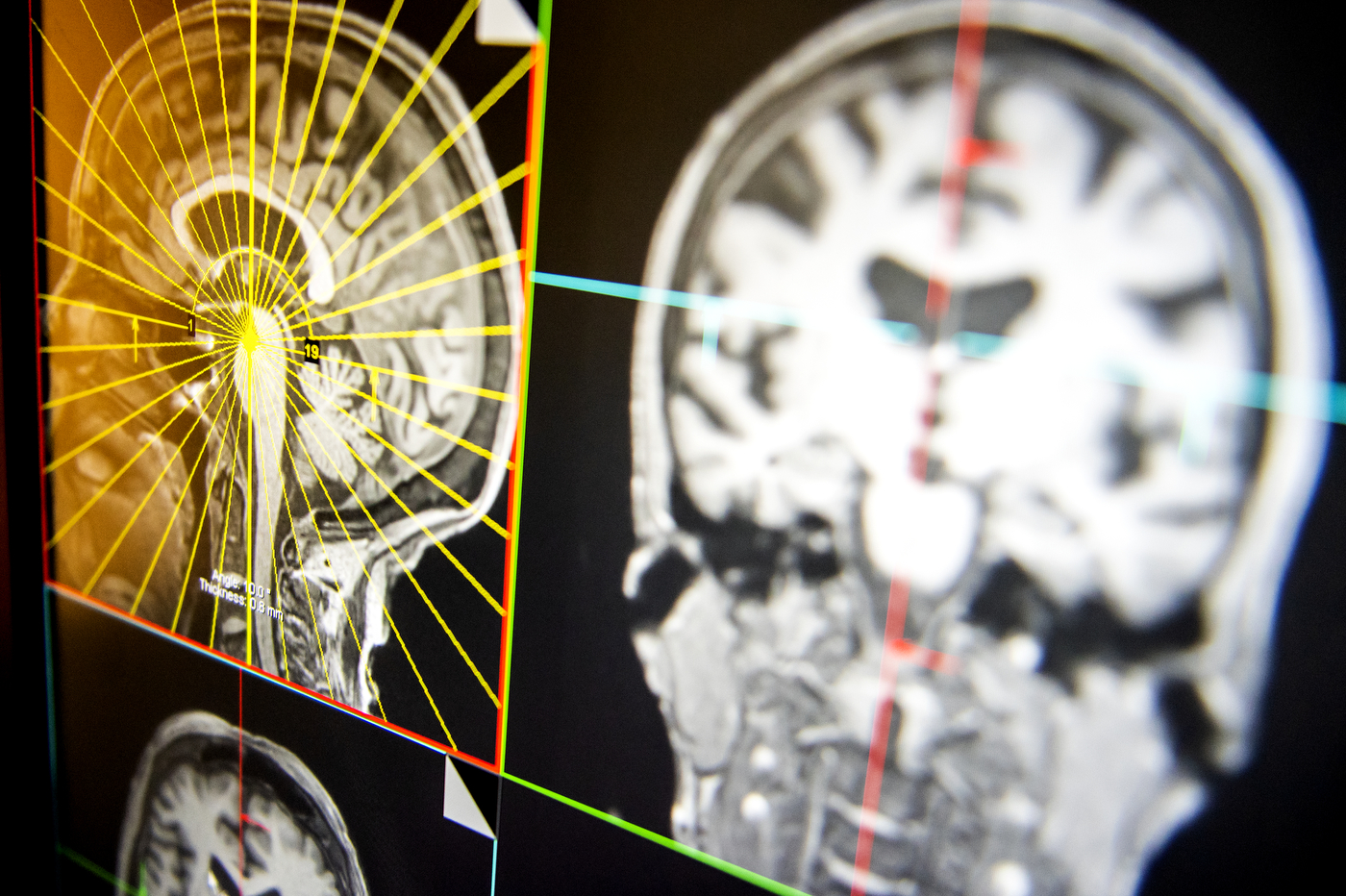

Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli, professor of psychology and director of the Biomedical Imaging Center, and Fred Bidmead, lead MRI research technologist, use MRI scans to study how blood flows in synchrony through different regions of the brain at rest. Photos by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Whitfield-Gabrieli, who also directs the Biomedical Imaging Center at Northeastern, says these numbers tell the story of a crisis and epidemic in teenage anxiety and depression.

“When you look at the stats, this is clearly a huge problem that we’re facing right now,” she says. “Emotional health has hit a low, and unfortunately, this then translates into things like suicide.”

For Whitfield-Gabrieli, the biggest problem lies in acting too late to address symptoms of mental illness from an early age. These symptoms, she says, generally go undetected until it’s difficult to address them, when somebody is in crisis, or when a person is already having suicidal thoughts.

Her team analyzed how blood flows in synchrony through different regions of the brain at rest. That resting state activity creates patterns, or networks, that Whitfield-Gabrieli and other researchers had previously linked to depression and bipolar disorder.

Used as biomarkers, these patterns of brain activity show that they can predict the progress of anxiety, depression, and attentional symptoms more accurately than other tools used to diagnose mental conditions, including questionnaires that psychiatrists use to assess mental health.

“That may actually be predictive of the future,” Whitfield-Gabrieli says. “But time and time again we’ve been finding that the brain metrics actually outperform these questionnaires in predicting the progression of symptoms.”

Conventional research on brain activity and psychiatric disorders has mostly focused on children who are at risk of depression, Whitfield-Gabrieli says. But to take it one step further, the study focused on a diverse sample of children who were not preselected based on genetic or clinical risk for psychiatric conditions.

“They weren’t selected for being at high risk for anxiety or depression, and yet, we can still find biomarkers that predict progression of these disorders,” she says.

The study focused on 54 seven-year-old children, analyzing patterns of activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, two regions of the brain associated with attention and mood. The researchers coupled that data with activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is important for focusing, controlling impulses, and other highly complex cognitive functions.

The team found that stronger associations of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex at age seven predicted attention problems at age 11. Also, weaker associations of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and subgenual anterior cingulate predicted anxiety and depression problems by age 11. The predictions were also successfully replicated on separate groups of children with and without a family history of depression.

Whitfield-Gabrieli says that now, the goal is to find even earlier indications of mental illness in brain images of infants, in addition to conducting wide-scale behavioral interventions that could involve techniques such as exercise and mindfulness meditation.

“There are a lot of behavioral interventions that we can do that have no harm and that might prevent the progression of a disorder,” says Whitfield-Gabrieli, adding that her work using mindfulness meditation with children in Boston schools has been shown to reduce stress.

That’s an approach that could start shifting the course of teenage anxiety and depression. And it could be the missing piece that connects thousands of brain-imaging studies on psychiatric disorders that have yet to fundamentally enhance treatment of mental illnesses.

“We’re finding cures for all of these other diseases, but we still need a huge help with psychiatry, because we don’t understand the pathophysiology of the disorders and what treatment to give them,” Whitfield-Gabrieli says. “That needs to change.”

This story was originally published on News@Northeastern on January 2, 2020.