The Aramaki Lab at Northeastern University, led by assistant professor Tsuguo Aramaki, is making exciting advances in the field of astrophysics. The lab is currently working on the GRAMS (Gamma-Ray and AntiMatter Survey) project, and the lab recently received a grant from NASA for this project.

We spoke to professor Aramaki about how his lab functions and the impact the GRAMS project is expected to have.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

- What is the goal of your research?

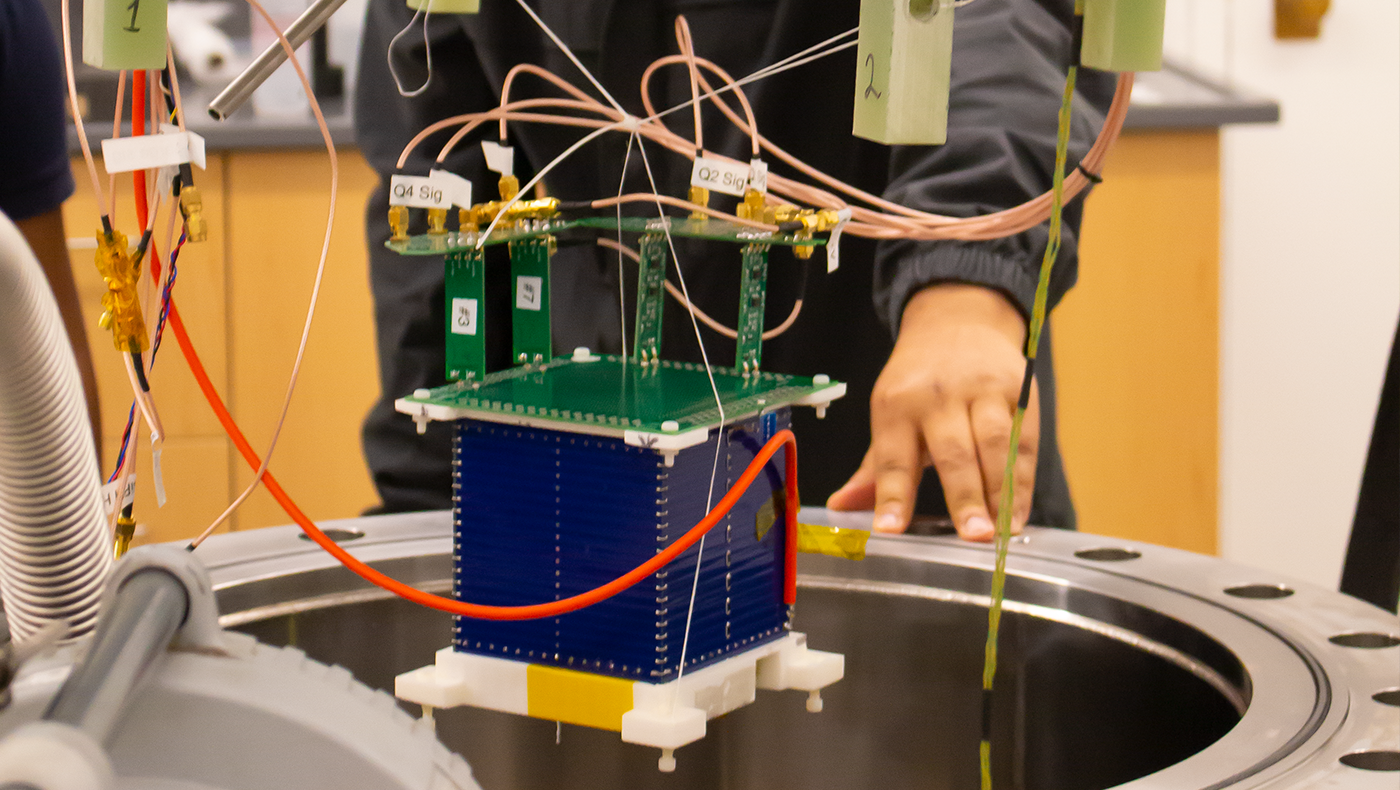

The goal of the GRAMS project is to study astrophysical observations with MeV gamma-rays while searching for dark matter with antimatter. The GRAMS project uses a LArTPC (Liquid Argon Time Projection Chamber) detector surrounded by plastic scintillators. Argon is cost-effective, so we can make our detector larger, which means we can have a better sensitivity. The larger the better! This means we will have a better chance to achieve our research goal.

- How will your research impact the field of astrophysics?

I believe that GRAMS can observe our universe uniquely with gamma rays in the poorly explored MeV energy domain, including annihilating dark matter and evaporating primordial black holes. With the GRAMS project, we are also capable of exploring dark matter parameter space via antimatter measurements. Especially low-energy antideuterons and antihelium measurements can offer background-free dark matter searches. I really hope that GRAMS will make a positive impact on the way we understand our universe.

- How does your past research with astrophysics contribute to your decision to pursue the endeavor stated in your grant?

When I reflect back on my academic career, I genuinely do think that all my past research projects and experiences have contributed to receiving a NASA grant for GRAMS. I conceptualized the GRAMS project a couple of years ago by drawing from my experiences and knowledge of GAPS and SuperCDMS. At first, I felt that the project was not convincing enough; however, I had input from many colleagues and continued to refine my ideas. And I found wonderful collaborators to work with along the way. There is a Japanese saying, “Experience is an asset,” which I strongly agree with.

- Who is helping you conduct this research and what responsibilities does this person/people have?

I currently have one postdoc, three Ph.D. students, and five undergraduate students (and two M.A. students and one undergraduate student in the past) who help me in the lab. Each person has different responsibilities, from data analysis to building the actual hardware. Although my students tend to work independently, they also work together when building instruments in the lab.

- What does a normal day in your lab look like?

We have daily morning meetings with senior members to discuss any issues encountered and how they can be resolved. During the problem-solving discussions, everyone has the opportunity to speak and present their ideas. We had many constructive and meaningful conversations, and each person contributed to the project in many ways! After the meeting, some stay in the lab to finish their tasks, while others work on data analysis at their office or go to class.

- Is there anything else we should know about your research?

The GRAMS collaboration is working towards the prototype flight scheduled in 2025/2026. At Northeastern University, we are building and optimizing a small-scale detector, MiniGRAMS, in our lab to demonstrate its performance for future balloon flights. It is an exciting time for our group, and we are now in the trial-and-error stage and trying to measure light and charge signals in the detector. I always tell my students to be creative and to think from a different perspective.

Photos by Noah Haggerty and the Science Media Lab.