It wasn’t the result the scientists wanted.

“When we noticed it changed color in light, we were super annoyed,” says Leila Deravi, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern. That meant the substance wasn’t stable enough for the applications Deravi had in mind.

But the disappointment was short-lived, as Dan Wilson, a research scientist at Northeastern’s Kostas Research Institute, quickly realized that the outcome could be turned into a feature rather than a bug.

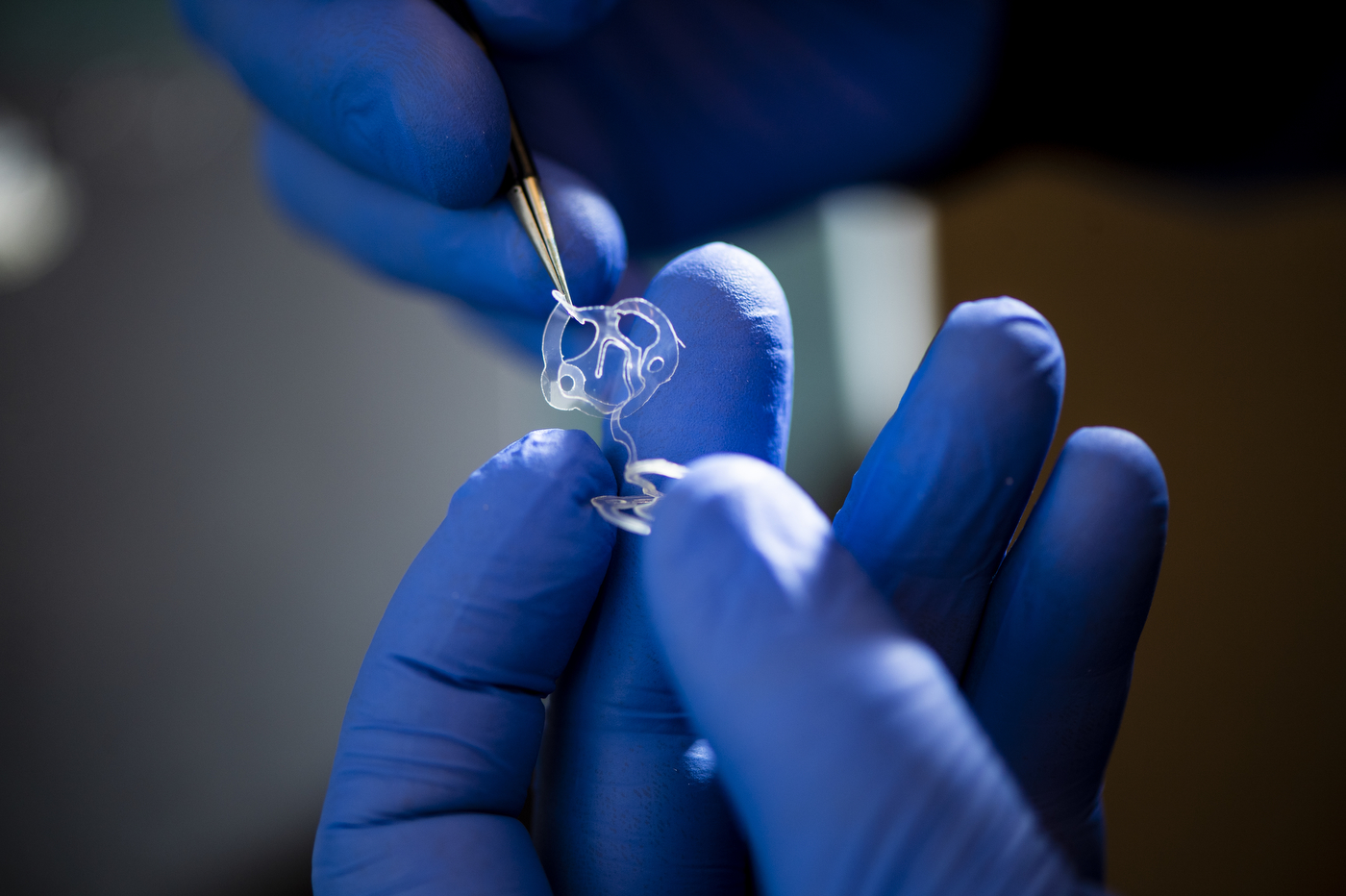

Wilson built on the unwanted chemical reaction to create dime-sized devices that change color when they’ve been exposed to a damaging amount of ultraviolet radiation, helping people prevent cancer-causing skin damage. The invention is essentially a tiny sticker that people could place on a shirt, hat, or bathing suit when they’re headed outside.

“We all know more or less that too much sun on a high-UV-index day is bad. But we don’t necessarily know how that translates to time in the sun,” Wilson says. “This is meant to provide a visual, qualitative indication of when you may have been in the sun for too long and you should consider spending some time in the shade or reapplying your sunscreen.”

The development of this device started not with humans, but with squid.

At the time, Wilson was a postdoctoral research associate in Deravi’s Biomaterials Design Group. The team studies how cephalopods—tentacled sea creatures such as octopus, squid, and cuttlefish—camouflage themselves to blend into their environment. With a particular focus on squid, the researchers have identified and isolated many mechanisms, pigments, and chemical reactions that enable the animals to alter their appearances with ease.

When the circuitous discovery occurred, Wilson was testing one substance critical to squid’s color-changing capabilities: a pigment called xanthommatin. The small molecule gives squid skin its visible color.

Deravi’s team had already found that xanthommatin could be manipulated to change color, and she hoped that it might be something that could be integrated into materials for a variety of applications such as apparel, or other consumer products. But in order for that to be possible, she says, xanthommatin would need to be stable and controllable in many environments.

So when Wilson noticed that xanthommatin would change color when left out on the lab bench in ambient natural light, Deravi was initially disappointed.

Read more on News@Northeastern.

Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University.