A new paper from Professor Steven Vollmer brought him back to his Ph.D. research on coral hybridization with a single objective: Introduce a healthy dose of skepticism into an ongoing debate in coral science about hybrid coral species saving the reefs.

The paper was published in the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington in April and focuses on a Caribbean coral called Acropora prolifera, which is a hybrid of two other coral species commonly known as staghorn and elkhorn coral.

Acropora palmata (Elkhorn Coral). Photo by William F. Precht

Many scientists working in coral research see A. prolifera as an example of hybrid vigor, where the hybrid species performs better than the two parents. Vollmer himself referred to A. prolifera as the “immortal mule” in a paper he wrote in 2002 because it can reproduce indefinitely by fragmenting asexually.

But Vollmer said because of that vigor, some scientists jumped to the conclusion that A. prolifera could be some magical cure for reef decline. He and his co-authors wanted to provide a different perspective.

“It was just reaching a crescendo of certain groups saying that somehow hybrids are going to rescue the reefs and these hybrids were a recent phenomenon,” he said. “We wanted to just set the record straight and show the genetic data and the new fossil data demonstrates that these hybrids have been around a lot longer.”

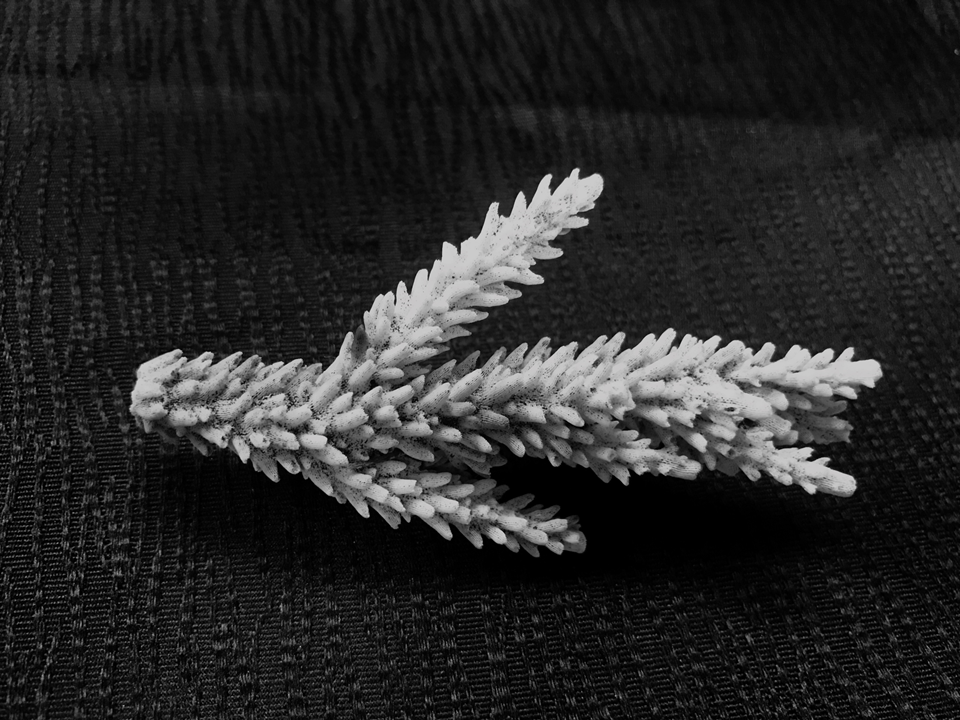

Acropora prolifera (hybrid). Photo by William F. Precht

The paper makes the point, using fossil analysis, that A. prolifera has existed on Caribbean reefs since the late Pleistocene era, which was between 120,000 and 5,000 years ago. That means this interspecies hybridization is not new, and therefore not a result of declining coral species making room for a hybrid, as many scientists hypothesized.

A lot of Vollmer’s research since his Ph.D. has centered on understanding white band disease, a deadly coral disease that has wiped out 95 percent of susceptible corals in the Caribbean. Most of that research involved experiments and other hands-on work. This paper, however, felt more like a “museum mystery hunt.”

“This paper basically was two colleagues, Bill Precht and Les Kaufman, pestering me for the better part of a decade to say, ‘Let’s write this paper,’” he said. “The discoveries were more based on conversations, which has never been the case for me.”

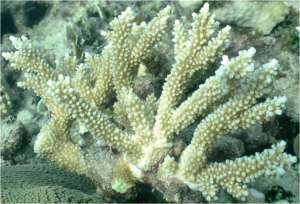

Acropora cervicornis (Staghorn Coral). Photo by William F. Precht

Moving forward, Vollmer has posed an interesting question that relates both these topics. One of the parent species, A. palmata, may have disease-resistant genes that it passes on to the hybrid when it mixes with A. cervicornis, the other parent. The hybrid can also backcross, or breed with the parent species, further mixing those genes around.

Vollmer wants to look at how those genes are moving between the three species: What genes are being filtered out because they are less viable? What genes, like maybe the disease-resistant ones in A. palmata, could be passed to A. cervicornis through mixing with a hybrid?

“The idea that’s most interesting and unexplored thus far is whether or not hybrids are more disease-resistant, and whether or not they’re passing A. palmata genes to A. cervicornis that make them more disease-resistant,” he said.