Co-ops are the cornerstone of a Northeastern University education. Applying classroom lessons to real world environments can be a transformational learning experience. So how does it work during an international pandemic?

Throughout the Fall 2020 semester, we’ll be checking in with COS co-ops to find out. Read about their unique Northeastern experiences and the ups-and-downs of COVID-19 on their work, their social life, and their thoughts on the future.

Read the first profile here and follow the series with the hashtag #COSCoop

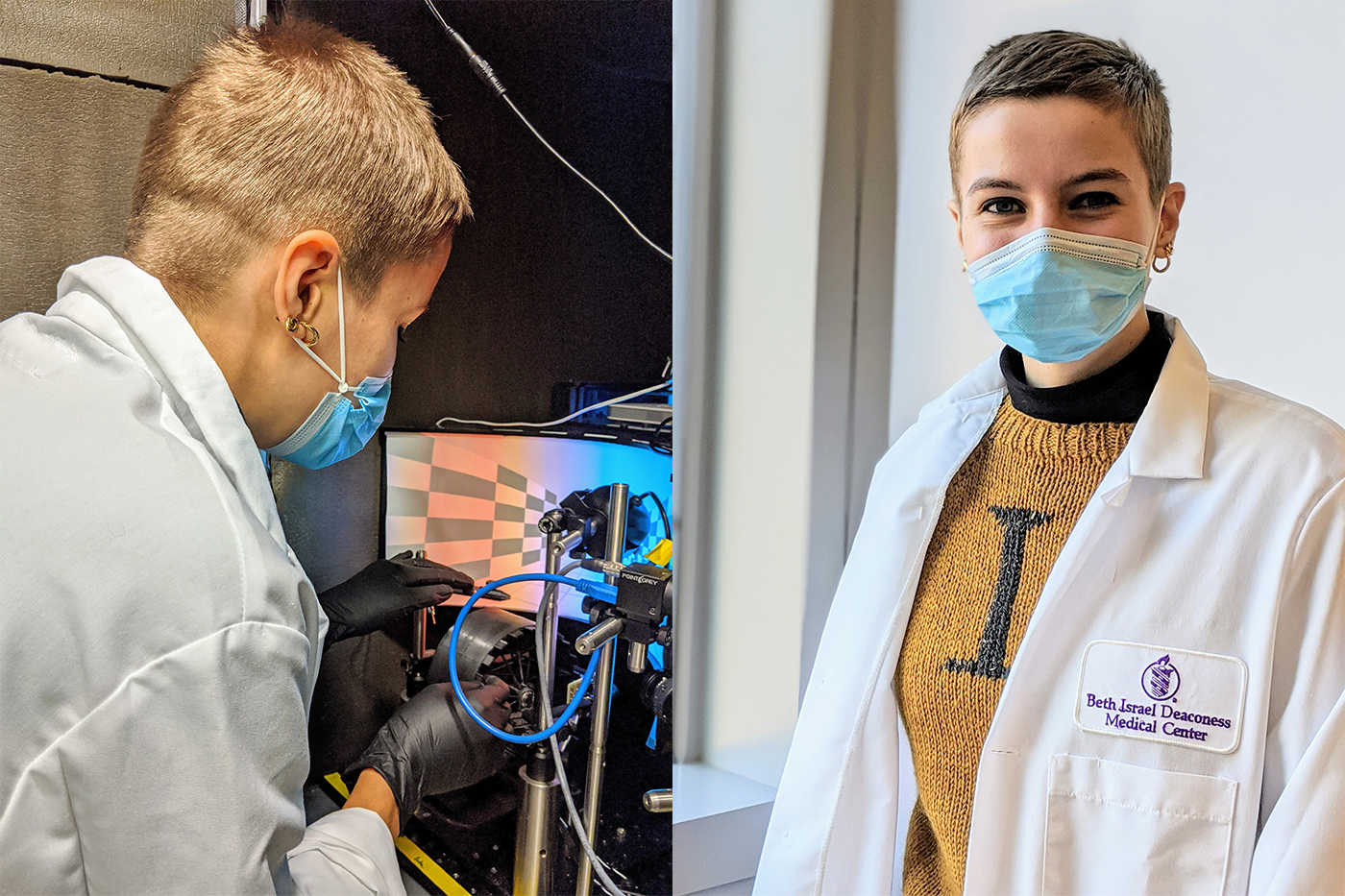

Meet Leilani Potgieter, Research Assistant at Harvard Medical School/Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Can you tell us what a standard day is like for you working there?

My job initially was helping researchers run behavior studies with mice to collect data. That role has changed because of the pandemic, so I’m doing a lot more widespread responsibilities than I was expecting. I’m mainly working with a postdoc to collect data for behavior studies. A typical day for me was doing studies in the morning and then doing data analysis remotely in the afternoon.

Things are a lot more flexible now that we are done running that specific cohort of mice on behavior, so I’m mainly helping with slicing brain tissue and getting slides ready.

How are you splitting your time between in-lab and at home?

I haven’t spent a full day in person in the lab since I’ve started. I’ll do maybe maximum six hours in person and then some days less, but I also work from home every day. So I’m still working 40 hours a week, but about half of my time is remote.

How has that work setup been going so far?

It’s kind of half and half for me. I really enjoy having the opportunity to work remotely and that I can start my day off in the morning at home, more relaxed, not having to run into the lab to get there on time. But I also like having a place to go to work.

What were your expectations when you first started and how has that changed?

It kind of changes depending on what phase we’re in. There’s a lot of steps in doing a study with mice: things like breeding, getting the mice used to being handled, etc. Then you’re collecting their behavioral data and analyzing the tissue. So things change on a week-to-week basis.

I have to keep checking in with my postdoc to see what it is that we’re up to this week. But I definitely am responsible for a lot more now that I’ve been trained. So from the beginning of my job to now, my postdoc is more comfortable leaving me alone to do certain tasks that I would not have been left alone to do prior. I’m progressing in my lab skills specific to this job, but I still wouldn’t say I’m anywhere close to being okay doing everything by myself.

Is this your first or second co-op and how is it helping shape your career thoughts?

This is actually my first co-op. I know it’s kind of strange for me to be a fourth year on their first co-op, but I studied abroad in my second year and that messed around with my schedule. I have worked in labs prior to this, just not on co-op, so I wasn’t going in blind.

One of the things that I’m noticing is the difference in dynamics between this lab and the previous labs that I’ve worked in. I’ve seen is that there’s a lot less communication and a lot less community, which I really valued in one of the labs that I worked in at Northeastern. I’m also learning that unfortunately I’m not a huge fan of working with mice.

I’m thankful that this co-op has helped me figure out what I want to spend my entire career doing. It’s really valuable to have a temporary position where I’m able to figure those things out without fully committing.

What have you learned from your co-workers?

What have you learned from your co-workers?

Some of my relationships with my co-workers are really great. It’s unfortunate that we don’t get to spend as much time together because of the pandemic.

Also, learning about what co-workers did before coming into the lab and what their plans are helped me realize it’s okay not have everything figured out yet. There are people at every stage of their scientific career working here, and there’s this unanimous sense that, sure, I have a plan for the next couple months, but do I really know what I want to do with my life? Not really. It’s nice to see that, everybody feels a little bit of imposter syndrome and everybody kind of feels as if they’re here and qualified to be doing these things, but still “iffy” on what where to go from here. So that’s heartening to know.

Has going from the classroom to the lab accelerated or altered your learning process?

Yeah, definitely. So one of the things that I always noticed in class before I had any real practical neuroscience lab experience was that it was hard for me to put the things that I was learning into context. Everything was abstract.

That was one of the things I was grateful for in this job and in my previous job—that when you’re slicing brains and studying a specific part using a method you’d learned about in class—you’re getting the visual context. You can then say: In this slice, I’m looking at the hippocampus here, and looking at the cerebellum there. That’s super valuable.

I think it’ll really help going forward in classes. Being able to learn about parts of the brain where I can say to myself, “I know where that is.” Putting it in context allows me to be able to understand the more abstract parts of neuroscience.

Studying the brain might feel unapproachable to some. How did you get interested in this program?

I decided I wanted to study neuroscience during my junior year of high school while watching Brain Games, the show by National Geographic. It was just Jason Silva on the screen saying “When you feel fear, your amygdala, it lights up… and here’s a picture of a brain… and this is all this stuff that’s going on. Now we’re going to show you this in-person study….” I thought, “That was really cool. I want to do that.”

With STEM in general, there’s a lot of people who have this idea that this is only for really smart people. That you really have to know what you’re doing at all times to study STEM, which is not true. All it takes is working with somebody that is familiar with your interests. Being able to have a conversation and learn what inspired them to do it so you can do it too. I’m really excited that I’ve been able to have that experience—to talk to my professors and talk to my coworkers—about what makes them excited about science. The stigma around neuroscience can be really difficult, but if there are other people just like you who can do it, then you can do it too.