Faculty Labs

News

Shells of their former selves: How sea snails have adapted to invasive predators

Over the past two decades, the Gulf of Maine has become a popular landing spot for invasive species from across the world, says Geoffrey Trussell, an evolutionary biologist and professor at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center in Nahant, Massachusetts.

“Lots of invasive species have arrived on our shores, mostly through ship ballast,” he explains. “So you have this confluence of significant environmental changes.”

Trussell has witnessed those changes on the ground — very, very low ground. Starting when he was a Ph.D. student in the 1990s, he has monitored the evolution of two common species of sea snails living off Maine’s coast, tracking how they have responded to changes in that environment and the resulting influx of predators. Among the most successful of these are predatory green crabs — small, brightly colored crustaceans that have surged north from the mid-Atlantic coast over the past few decades and love to feast on tidal snails.

In a recent paper published in the academic journal Science Advances, Trussell and collaborator James Corbett document how the snails (Nucella lapillus and Littorina obtusata) have evolved in response. In brief: they’ve grown thicker shells.

Read more from Northeastern Global News.

Illustration by Renee Zhang/Northeastern University

Squid are some of nature’s best camouflagers. Researchers have a new explanation for why

Nature is full of masters of disguise. From the chameleon to arctic hare, natural camouflage is a common yet powerful way to survive in the wild. But one animal might surprise you with its camouflage capabilities: the squid.

Capable of changing color within the blink of an eye, squid, along with their cephalopod relatives octopi and cuttlefish, have used their natural camouflage to survive since the age of the dinosaurs. However, scientists still know very little about how it all works.

Leila Deravi aims to change that.

An associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern University, Deravi’s recently published paper in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C sheds new light on how squid use organs that essentially function as organic solar cells to help power their camouflage abilities. Deravi says it’s a breakthrough in how humans understand these “super-charged animals,” one that could impact how we humans interact with the world.

Read more from Northeastern Global News.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

Patagonian ‘living rocks’ trace their origins to the beginning of life on Earth

In the Patagonia region of southern Chile, there are “living rocks.”

While that’s what the locals say, Veronica Godoy-Carter, associate professor of biology and biochemistry at Northeastern University, says it’s a little more complicated than that.

“They’re actually little mountains,” she says, of “giant biofilms that are billions of years old. Literally billions.”

To put that in perspective, the Earth is thought to be about 4.5 billion years old, which means these “rocks” — really bacterial biofilms (a sheet of bacteria only a few cells thick) — have been around a long, long time.

Over the eons, these biofilms have piled up and calcified into forms that look like rocks called stromatolites.

They predate humans, our primate ancestors, maybe even multicellular life itself.

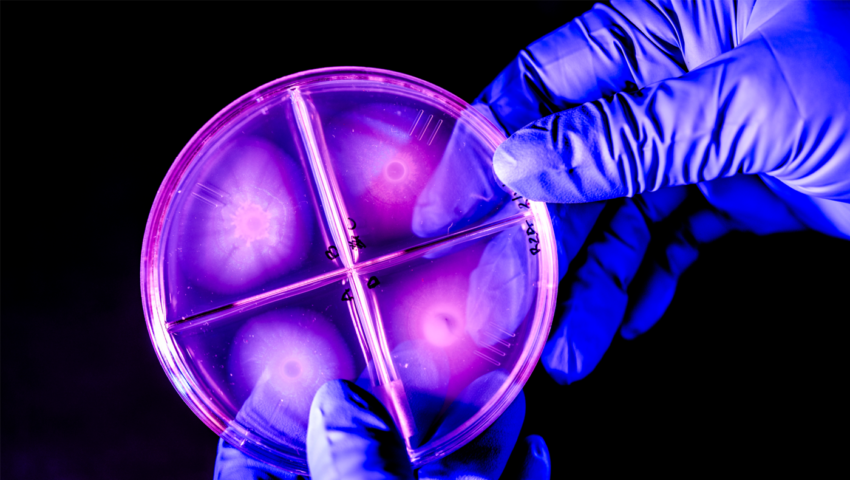

Now Godoy-Carter has sequenced the genome of one of these bacterial colonies, a species within a genus called Janthinobacterium, which is found in soil and water and has a distinctive violet color.

Read more from Northeastern Global News.

Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

The ‘dark matter’ of nutrition: How AI and network science are transforming our understanding of food and health

Network science and artificial intelligence can identify food molecules that negatively affect health as well as alleviate disease by proposing dietary changes, a Northeastern expert says.

Since the human genome was decoded in 2003, Albert-László Barabási — a distinguished professor of physics at Northeastern University and director of the Center for Complex Network Research — has used network science to map out connections between proteins in human cells. “That’s where network medicine comes in,” Barabási says.

Eventually, network medicine will be able to provide personalized dietary recommendations and treatments, he says, based on an individual’s genetics, diet and disease stage.

Read more from Northeastern Global News.

Getty Images