People

We are teachers, leaders, researchers, advisors, business professionals and students. Welcome to Northeastern’s College of Science

News

Unveiling the Potential of Bismuth Ferrite in Antiferromagnetic Spintronics – A Q&A with Professor Paul Stevenson

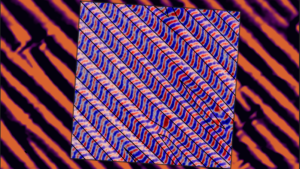

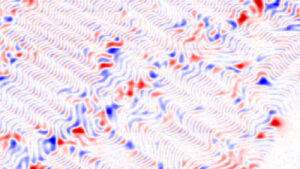

In their recent publication, physics assistant professor, Paul Stevenson, and his collaborative team from Northeastern University, Brown University, Rice University, and University of California Berkeley reveal groundbreaking advancements in utilizing isolated spins in solids. Their work, enabled by the Quantum Materials and Sensing Institute, pioneers ultrasensitive nanoscale sensors and quantum communication technologies. Through interdisciplinary efforts, they delve into probing nanoscale biophysical dynamics and advancing antiferromagnetic spintronics, particularly in electric-field controllable magnetic devices using materials like Bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3).

To learn more about their research, I spoke with Paul Stevenson discussing the implications of new materials in the world of physics and the importance of collaborative research. Read the publication, “Persistent anisotropy of the spin cycloid in BiFeO3 through ferroelectric switching,” here.

What first drew your attention to antiferromagnetic spintronics, particularly in relation to controlling spin configuration on nanometer scales?

The overall motivation is driven by need to make more energy-efficient computers. The amount of energy that we spend doing computation is growing much faster than we generate energy. This drives the need for low power and more efficient ways to do computations, so we need to find alternatives to serve traditional silicon transistors.

Finding alternatives is difficult because we’re already so good at making silicon devices, so there isn’t much room to keep improving. It’s scary and exciting because it suggests we should start looking elsewhere and for new types of materials that aren’t in conventional silicon chips, which is where bismuth ferrite comes in.

Could you explain why bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) is considered a promising material for electric-field controllable magnetic devices, given its multiferroic properties?

The main attractive things about bismuth ferrite are that we can change its magnetic properties with voltages and that it works at room temperature. There are a lot of interesting multiferroic materials from a physics and fundamental science perspective, but many of them only work at very low temperatures. If we’re trying to be energy efficient, cooling things down to liquid nitrogen temperatures is the opposite of what we’re looking for.

From a physics perspective, it’s interesting because a lot of very complicated behavior bundled into one package. The things that make it useful (that the different types of order all talk to each other) also make it difficult to understand, which is why it’s taken such a long time to start maturing as a technology.

Piece by piece, we are learning how all these different parts fit together. How magnetism interacts with its response to electric field and how that does or doesn’t couple to strain in the material, and how that changes depending on the different ways that we make or treat it.

What were some of the key challenges you encountered during your research, and how did you overcome them?

This is one of the more straightforward research projects I’ve done, thanks to the new tools and equipment in the Quantum Materials and Sensing Institute. There’s a lot of complicated interpretation that goes into the data, however, but thankfully we’ve had a lot of support from collaborators and a lot of great work that’s been done in the field already that helped us understand what we were seeing.

The conventional challenged with this research is that the magnetism varies on length scales of tens of nanometers, which makes it great in terms of being able to make things very compact b But it becomes very difficult to find experimental techniques that can be sensitive and reach down to those length scales.

That’s where the scanning diamond magnetometer that we have at the Quantum Materials and Sensing Institute comes in because it combines that sensitivity and that very high spatial resolution.

How do you envision your study’s findings influencing future research directions in antiferromagnetic spintronics?

The field of antiferromagnetic spintronics is a fascinating and growing field by itself. Antiferromagnetic spintronics is a subset that’s still growing and becoming more and more exciting because it has a lot of potential for very high-speed operation. Often in this field, it’s always a case of experimental techniques catching up to the need for what we don’t know. It’s really an area where big science questions are driving the development of new techniques.

In the case of Bismuth Ferrite, there are lots of models out there lots of global probes that say that some sort of interesting magnetism is present, but there’s really no technique that’s able to directly correlate it with other experimental imaging methods like we can or watch how it changes as we apply a voltage. In this paper, we measured the structure of the polarization and magnetism, and then overlayed them on top of one another. We can see that there’s a perfect one-to-one correspondence; we don’t need to do any complicated analysis to convince ourselves they’re correlated.

In a way, it’s a very basic capability that we’ve been able to develop, but a very important one. We want to see in real space what’s happening with magnetism without having to model or infer what’s happening from a less direct probes.

Lastly, what excites you the most about the potential applications of BiFeO3 and similar materials in the development of advanced spintronic devices?

The thing that really excites me about bismuth ferrite is the range of different behaviors we can get from the slightest tweaks to the materials in the system. We can get lots of different types of magnetic ordering all coming from what looks like almost the same structure, which suggests there’s a huge amount of physics and interactions between all these things that we can access and start to systematically explore in these systems.

The applications in low power or high-speed electronics are important. But what really gets me excited is the physics potential. There’s still a long time before this becomes a commercially-available, scalable technology, but we’ve made an important step in showing that we can deterministically control the magnetism in systems like these.

Photos courtesy of Paul Stevenson

The untold story of how two Northeastern professors analyzed moon rocks for NASA a half-century ago

The rocks were billions of years old. But they were new to the Earth. They were sent by NASA in 1972 via special delivery to Robert Lowndes and Clive Perry, physics professors at Northeastern University, who opened the boxes in their secured labs in the basement of Dana Hall.

“It was very exciting,” Lowndes says.

The rocks and the accompanying soil samples had been collected from the moon by the Apollo astronauts. Lowndes and Perry were among the small, initial group of U.S. professors selected by NASA to perform experiments on the moon rocks.

The first shipment arrived two years after astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin became the first human beings to land on the moon.

“The rocks were quite small, an inch or so is what I remember,” Lowndes says. “And then we also got the soil samples, which were powders.”

The Northeastern physicists would receive multiple shipments of lunar samples that had been retrieved by the astronauts of Apollo missions 11, 12, 14 and 15 from 1969 to 1971. The rocks and powders were arguably the most precious materials in the world at that time — more valuable and rare than any earthbound piece of jewelry or source of energy.

Read more from Northeastern Global News

Photo by Matthew Modoono

What time is it on the moon? We may soon know, thanks to NASA project

From sundials and water clocks to modern atomic timekeeping, methods for telling time on Earth — to mark the divide between night and day, month to year, etc. — have evolved over thousands of years.

Now, scientists are bringing their technological knowhow to the moon in order to establish time standards there and elsewhere in space.

The White House has directed NASA “to establish time standards at and around celestial bodies other than Earth,” instructing the agency to “develop celestial time standardization with an initial focus on the lunar surface” by December 2026.

Arun Bansil, university distinguished professor of physics at Northeastern, says that time functions slightly differently on the moon because the gravitational force is weaker there than on Earth.

Northeastern Global News spoke to Bansil to learn more about the science behind the White House’s latest project. His comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Read more from Northeastern Global News

Photo by Getty Images

Exploring the Role of Citizen Science in Research and Community Engagement with Damon Hall

With the excitement of his recent publication, associate professor of Environmental Science and Public Policy, Damon Hall, met with me to discuss his research on the importance of citizen science.

“Citizen silence: Missed opportunities in citizen science” can be accessed here.

What initially sparked your interest in citizen science and its role in research?

My interest was initially sparked by the realization of significant gaps in our understanding of water resources, particularly in smaller streams where data is often lacking. In the U.S., the U.S. Geological Survey’s national river gauge system focused on collecting streamflow conditions from major rivers, leaving many smaller tributaries unmonitored. Citizen science offers a solution by empowering people to contribute to gathering crucial environmental data.

I was also curious about why people participate in citizen science and what are the possibilities of this relationships for scientists and society. My research focuses on stakeholder engagement and leveraging citizen expertise to enhance decision-making processes for experts and scientists. I explore ways to meaningfully engage citizens in these endeavors, aiming to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and community involvement for better environmental decisions. Citizen science promises to enrich society’s and the sciences’ understanding of environmental systems for making more informed decisions for sustainable resource management.

How would you define the term “citizen science” for someone unfamiliar with the concept?

Citizen science utilizes the public’s participation in some facet of scientific research, ranging from data collection to analysis to question and study design.

One key advantage of citizen science is its ability to access data from locations that may be inaccessible to scientists or process and analyze large quantities of data. Physical proximity to data sources is crucial, and citizens often possess valuable knowledge about their local environments, such as identifying erosion spots along rivers or understanding intricate yet observable ecological dynamics. Additionally, citizen scientists can provide environmental information that complements existing datasets, enriching our understanding of complex ecological systems.

What are some common challenges faced by researchers when engaging with citizen scientists, and how do you suggest overcoming these challenges?

The short funding cycles of scientific research, often 2-4 years, challenge the establishment of lasting citizen science initiatives. To overcome this, scientists must design studies that are mutually meaningful to both scientists’ and communities’ interests. This increases the likelihood that the project takes on a life of its own.

Another common challenge with citizen science projects is scientists’ myopic attention to data which can lead to treating participants as data collection instruments. This overlooks the expertise of local participants and missed opportunities to improve the outputs of the science by learning from them. Beyond data collection, it’s essential to explore how people want to engage with the project. In environmental topics concerning shared natural resources, participants are often driven by personal interest. Researchers should consider other ways the project can meaningfully connect to these motivations beyond engagement with data.

In your opinion, what are the key differences between a data-centered approach and a relational approach to citizen-science research?

In citizen science, there’s a spectrum of participation, from those who contribute data passively to others who seek a more involved, relationship-centered approach. The latter emphasizes collaboration, where participants provide feedback on data usage and help shape the project’s outcomes to meet their community’s needs. This approach values the practical application of data, ensuring that models and maps created are relevant and usable by citizens.

Central to the relational-centered approach is understanding stakeholders’ interests and finding common ground for collaboration. By actively involving citizens in discussions about data usage and product development, scientists can tap into local expertise and ensure that the project aligns with community needs. This collaborative process fosters mutual understanding and ownership of the project’s goals.

Maintaining regular contact with active citizen scientists is essential in this approach, allowing scientists to stay informed about community feedback and adapt the project accordingly. The emphasis is on continued engagement and dialogue, where scientists express gratitude for contributions and seek ways to make the data useful and accessible to participants, thereby nurturing a collaborative and mutually beneficial relationship.

What do you hope the future holds for citizen science, both in terms of research outcomes and community engagement?

Continued enthusiasm for citizen science participation is crucial for both scientists and citizens alike! Ultimately, the aim of science is to generate knowledge that benefits science, society, and for fields like environmental science, informs policy. By embracing citizen science and valuing participant input, scientists can make their research more relevant and impactful for society at large. Listening to the voices of citizen scientists enhances the meaningfulness and utility of scientific knowledge, bridging the gap between research and real-world applications.

Photos courtesy of Damon Hall