Species Spotlights

Learn more about the intertidal species that share our rocky coastline!

American Lobster

Our educational aquaria at the Marine Science Center house several American Lobsters featuring unique coloring. Lou (1st photo), pictured here snacking on a frozen sea urchin, is a large male lobster. Neptune (middle) is a 2-pound young male blue lobster. Jackie (3rd photo) is a 1-pound young female calico lobster.

How do lobsters get these unique colors?

Normal brown lobsters have a pigment called astaxanthin attached to a protein called crustacyanin. When you cook a lobster, the heat breaks this bonding, freeing the astaxanthin and turning the lobster red.

Rare colored lobsters (like calico, blue, or yellow ones) have astaxanthin attached to different proteins instead of crustacyanin. These different protein combinations, likely due to genetic anomalies, change how light reflects off the shell, creating unusual colors like yellow, dark blue, or multi-colored patterns. Approximately 1 in 2 million lobsters are blue. Jackie’s calico coloring is only found in approximately 1 in 30 million lobsters

A lobster’s diet can also affect its shell color. Lobsters that eat mostly small fish (instead of shrimp and crabs) get less astaxanthin in their diet, which can result in lighter colored shells like pale blue, white, or “cotton candy” pink.

Lobster Color Math 101:

astaxanthin + crustacyanin = brownish/greenish ’normal’ lobster coloring

less astaxanthin + more crustacyanin = blue lobsters (like Neptune – 1 in 2 million!)

astaxanthin + crustacyanin + other protein pigments = Calico or “freckled” pattern (like Jackie – 1 in 30 million!)

no astaxanthin, crustacyanin, or any other pigments = albino lobsters

Lobster research at the Marine Science Center

The Grabowski Lab conducts research on marine ecology. These scientists focus on improving the management of economically important species, such as lobsters, cod, herring, monkfish, and striped bass, and coastal habitats including oyster reefs, seagrass beds, salt marshes, kelp forests and cobble bottom. We also examine how the perceptions, knowledge, and social capital of coastal communities influence their decision-making on environment issues such as shoreline hardening, resource harvesting, and climate hazard preparedness.

For example, one of their recent papers explored startling changes in marine habitats as climate change is causing fish to move to new areas. Black Sea Bass, which normally live in warmer waters, are now moving north into the Gulf of Maine where lobster fishermen work. Scientists asked lobster fishermen what they’ve been observing because the fishermen spend lots of time on the water and notice changes that scientific surveys might miss. The fishermen reported seeing more Black Sea Bass during warmer years, and there are concerns that Black Sea Bass might eat lobsters and compete for the same ocean habitat.

This information from fishermen helps fill important gaps in scientific knowledge about how warming ocean temperatures are changing the ecosystem and affecting different species in the Gulf of Maine. Understanding these changes can help make better decisions about managing fisheries, including whether fishermen should try to catch and remove Black Sea Bass to protect the lobster population.

Green Sea Urchins

These small, spiny echinoderms use their hundreds of tiny tube feet (located between their spines) to slowly crawl across rocks and seaweed. They’re herbivores, using a special mouth structure on their underside with five teeth – called an aristotle’s lantern – to scrape algae off rocks and eat seaweed.

Urchins are relatives of sea stars and sand dollars; all these echinoderms have radial symmetry, with round bodies radiating out from mouths in the center, and are named for the spines or bumps covering the outer surface of the bodies of many of them (Greek root word echino- meaning spiny; Latin root word -derm meaning skin). Urchins have been living in Earth’s oceans for about 450 million years, which means they were around long before the dinosaurs!

Urchin research at the Marine Science Center

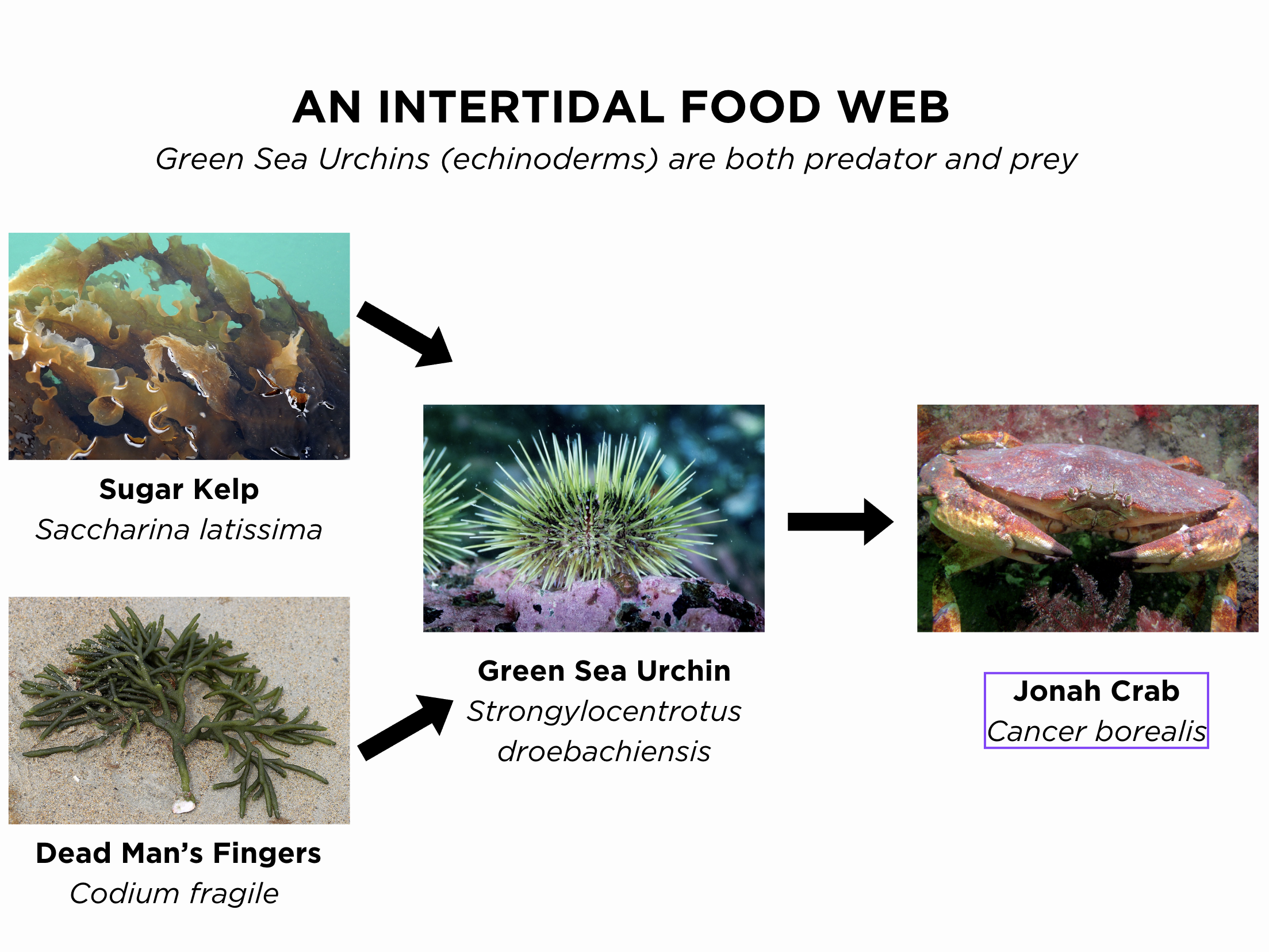

Nicole Peckham, a PhD student in the Kimbro Lab at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center, studies predator-prey interactions. One of the questions she is exploring is how green sea urchin behavior is influenced by the presence of Jonah crabs, a common predator.

Supplied with their favorite algae, Saccharina latissima (Kelp), and the less favorite Codium fragile (Dead man’s fingers), the urchins are able to move around their tanks while the Jonah crabs are confined in smaller enclosures in the same tanks.

Nicole and her team observed and analyzed any changes such as diet, feeding habits, and movement in the tanks to learn more about these interconnected species.