COS News

News

A new report from a group of Northeastern researchers explores across disciplines how biotech can ensure safe, sustainable life beyond Earth.

The key to international space cooperation is developments in biotechnology, Northeastern researchers say

News

The NeuroPRISM lab, led by assistant psychology professor Stephanie Noble, makes tools that pave the way for reliable and reproducible neuroimaging of the brain.

Precise maps of the brain’s deepest corners are made possible through tools developed by these Northeastern researchers

Showing 149 results in Research

Ashwagandha is having a moment. These researchers opened the door to more life-altering benefits

Ashwagandha, a popular supplement, is known for its effect on stress and sleep. Professor Jing-Ke Weng recreated its compounds in yeast, making a potential factory for its many benefits.

How living and working under the sea fills aquanauts with wonder and awe. The phenomenon is called the “underview effect.”

Professor Brian Helmuth studies how living underwater can create a mind-blowing effect similar to what astronauts experience in space.

These researchers flew a particle detector above Antarctica, hoping to find evidence of mysterious matter

Assistant Professor Tsuguo Aramaki has spent 20 years developing a weather balloon-borne particle detector to record indirect traces of dark matter. It recently launched in Antarctica.

A ‘stunning’ new map of dark matter reveals insights into this mystery of the universe

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, researchers including Professor Jacqueline McCleary, created the highest-resolution map yet of dark matter, the virtually invisible material that makes up about 80% of the universe’s matter.

What is dark energy? Scientists shine new light on outer space’s biggest, invisible question

The final results from the six-year Dark Energy Survey show there are still more questions than answers but will impact astrophysics for decades, Northeastern’s Jonathan Blazek said.

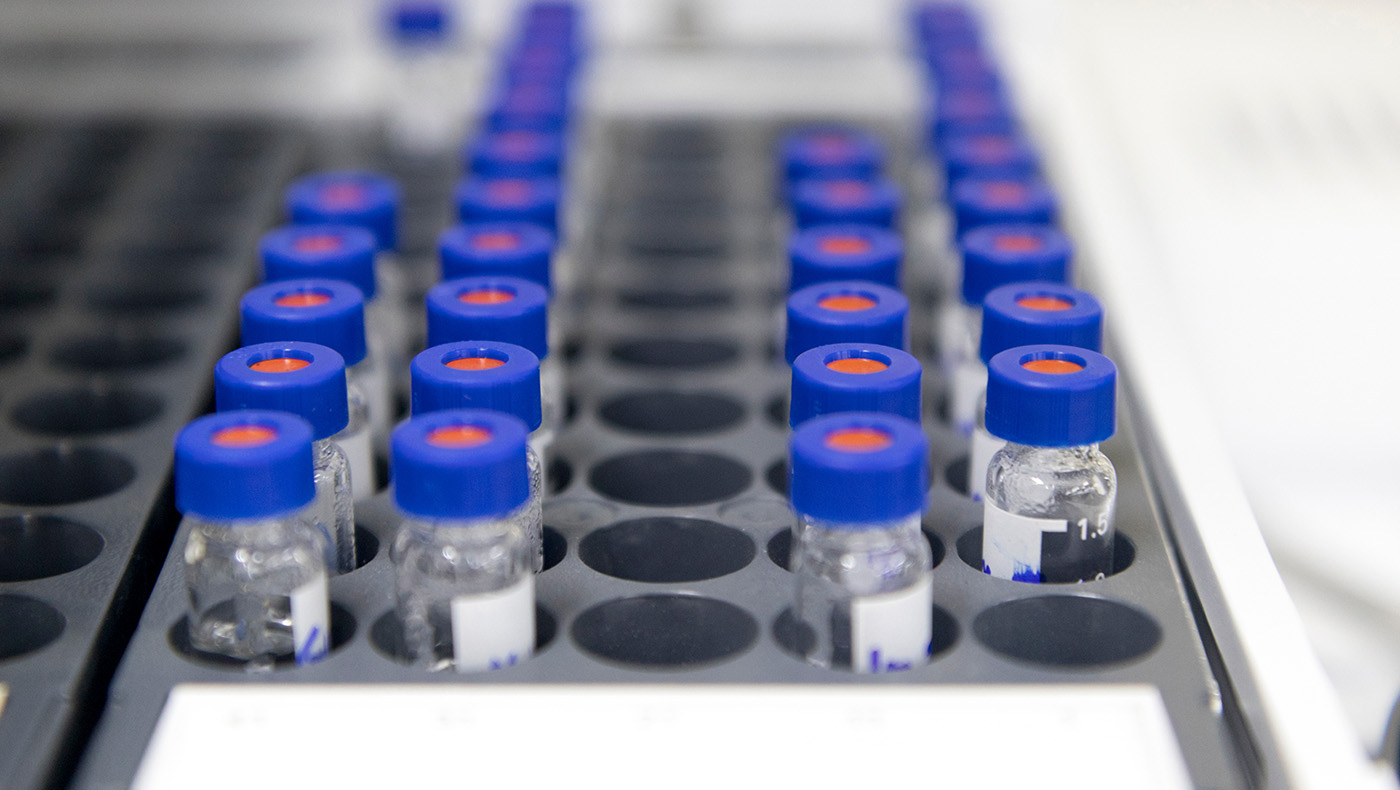

Mass Spectrometry Facility awarded grant to advance single-cell proteomics research

Northeastern University’s Mass Spectrometry Facility has been awarded a $2.2 million research infrastructure grant from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (MLSC) to build a cutting-edge core supporting single-cell proteomics research. The award, through the Center’s Research Infrastructure program, will establish a fully integrated pipeline that enables researchers to measure proteins at single-cell resolution, filling a […]

European Physical Society honors professor’s groundbreaking contributions to the physics of complex networks

Northeastern professor Alessandro Vespignani earns the European Physical Society’s top award for helping to lay the foundation for physics models of contagion.

In treating soccer like a language, these researchers can predict the next word

Brennan Klein, with the NetSI Sport research group, uses network science to treat sports and games like conversations.

The rubber in artificial turf decays into a potentially dangerous chemical cocktail, new research shows

New research by Zhenyu Tian, an assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, examines the complex and potentially dangerous miasma of chemicals released by crumb rubber, a fill material used in many artificial turf fields.

Rare earth element extraction can be doubled with this new technique

New research led by Damilola Daramola has identified a method of extracting rare earth elements from mining waste that is two to three times more efficient than previous approaches.

Why we remain attached to the music of our youth

Juliet Davidow, assistant psychology professor, argues that the social rewards when listening and experiencing music in our younger days helps ‘encode’ it onto our memories.

How string theory helped solve a mystery of the brain’s architecture

Scientists long thought neurons minimized connection lengths, but neuronal maps told a different story. New research by Albert László Barabási uses string theory mathematics to explain why.