Ah, fall. The season of apple-picking, cozy fireside gatherings, hearty food, and the sneaking sense that winter’s icy gusts are breathing down your neck.

You can try to outrun it: Add a cinnamon stick to your hot apple cider and settle blissfully into a willful ignorance of what is just around the corner. But, it’s no use. Let’s instead look to the trees for example. They’re not ignoring winter’s freezing death grip; they’re preparing for it.

Each year as the days grow shorter and the weather cooler, broad swaths of the United States forestry transform from lush green foliage into fiery reds and resplendent yellows, offering viewers a natural masterpiece. At peak foliage, the trees appear to stage an impassioned, dramatic performance that rivals the best films; serving up the kind of elaborate transformation that would win Oscars, were they nominated.

Not so fast.

“What you’re actually seeing is the trees conserving energy,” said Aaron Roth, a biologist at Northeastern.

Deciduous trees—the kind that have broad leaves, such as maple, oak, and hickory trees—lose water through their thin, delicate leaves throughout the year, Roth explained. This isn’t a problem in the summer, when trees can pull water up from their roots and there’s enough sunlight to be absorbed by the hungry plants.

As casual flora enthusiasts, you’ll recall that plants generate energy from sunlight through a process called photosynthesis. Trees produce chlorophyll, a green pigment that absorbs light. That light is then turned to energy that feeds the trees. During the summer growing season, trees produce chlorophyll as fast as they use it.

In the winter, when both water and sunlight are harder to come by, producing so much chlorophyll takes more energy than it’s worth.

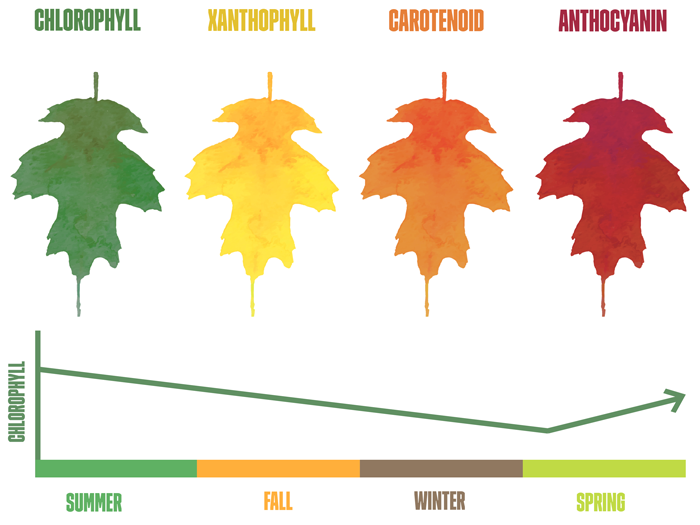

So, Roth said, trees slowly produce less and less chlorophyll. As the green pigment fades, other pigments that have been hidden underneath emerge. Xanthophyll is what gives leaves a yellow color; carotenoid an orange color; and anthocyanin a red color. All three of these pigments are always present in leaves, but in the summer they’re covered by the outsize amount of chlorophyll.

“The dominant color is green because it’s the most efficient for photosynthesis,” Roth said.

But, back to fall. Trees slow down their metabolism (the production of chlorophyll) in order to conserve energy for the winter. As less chlorophyll is produced, underlying pigments in the leaves become visible, creating foliage that draws leaf-peepers from far and wide.

Graphic by Hannah Moore

As casual flora enthusiasts, you’ll recall that plants generate energy from sunlight through a process called photosynthesis. Trees produce chlorophyll, a green pigment that absorbs light. That light is then turned to energy that feeds the trees. During the summer growing season, trees produce chlorophyll as fast as they use it.

In the winter, when both water and sunlight are harder to come by, producing so much chlorophyll takes more energy than it’s worth.

So, Roth said, trees slowly produce less and less chlorophyll. As the green pigment fades, other pigments that have been hidden underneath emerge. Xanthophyll is what gives leaves a yellow color; carotenoid an orange color; and anthocyanin a red color. All three of these pigments are always present in leaves, but in the summer they’re covered by the outsize amount of chlorophyll.

“The dominant color is green because it’s the most efficient for photosynthesis,” Roth said.

But, back to fall. Trees slow down their metabolism (the production of chlorophyll) in order to conserve energy for the winter. As less chlorophyll is produced, underlying pigments in the leaves become visible, creating foliage that draws leaf-peepers from far and wide.

This story was originally published on News@Northeastern on October 22, 2019.