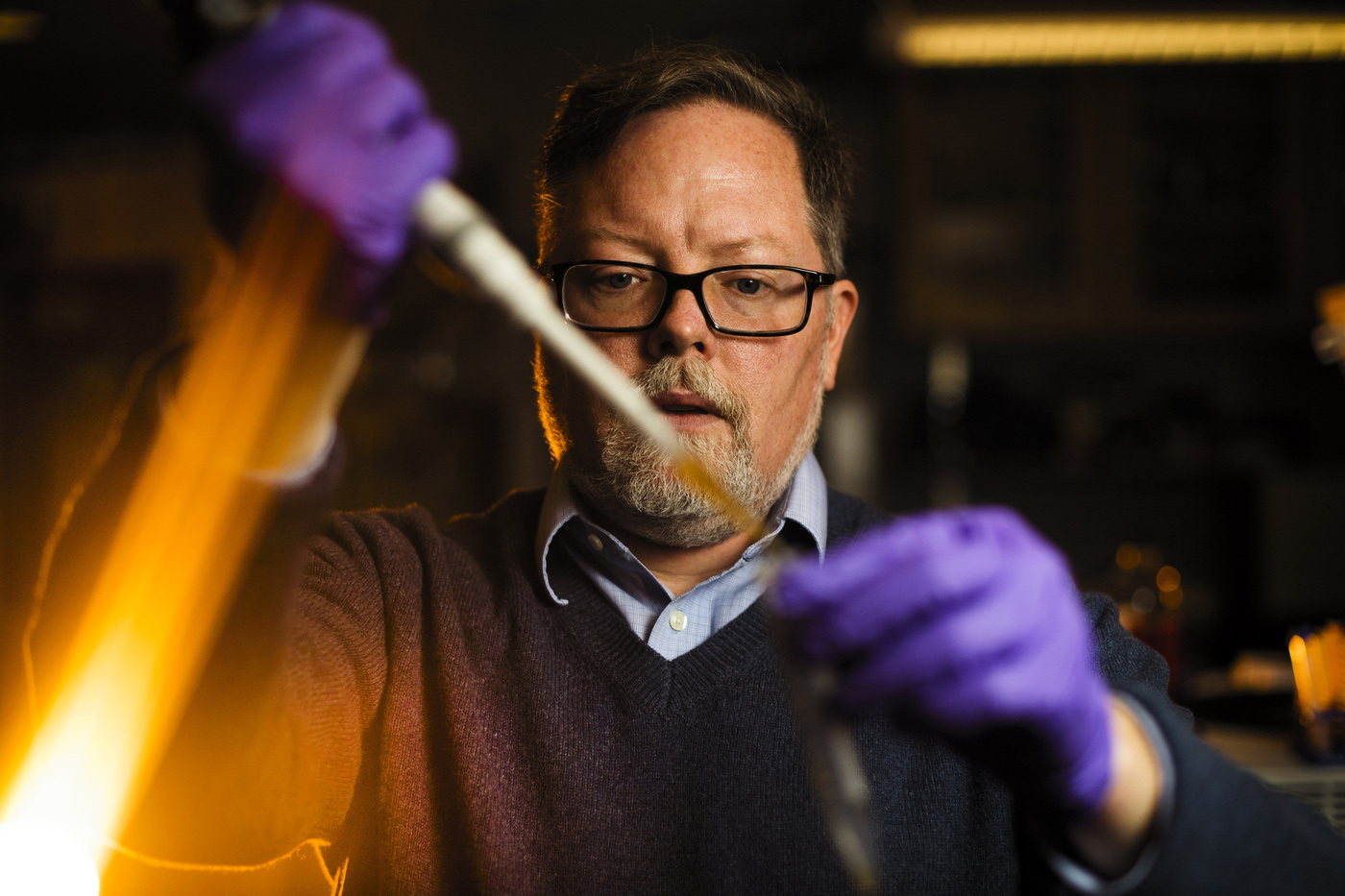

Life expectancy in the United States has been declining since 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thomas Webster, a chemical engineering professor at Northeastern, believes that medicine can do more to help Americans live longer.

“If your system is not doing what it’s supposed to, it must be broken,” said Webster, who is the Art Zafiropoulo Chair in Engineering. “So the key question is: What are we doing to solve this?”

The solution is to think small, said Webster, who was recently elected as an Overseas Fellow to the Royal Society of Medicine, a U.K.-based organization that encourages informed debate to improve the science, practice, and organization of medicine.

Webster’s lab at Northeastern develops medicine and technology at the nano-scale.

“What gets a lot of people in the medical field excited about nanotechnology is that size scale can penetrate your skin,” Webster said. It can also pass through the intestinal wall, the blood-brain barrier, and the more porous parts of bone. “That whole size range is just incredible.”

These properties allow nanoparticles to penetrate biofilms formed around persistent infections, deliver treatments without requiring invasive procedures, and more effectively target specific diseases. But the approval process for new treatments is slow, and with good reason, Webster said.

“Where do those particles go if they miss their target?” Webster asked. “Although you have extreme promise for where these particles can go, you also have opened up a Pandora’s box for where they can go.”

Webster is pursuing nanotechnology from a variety of angles. While his lab pushes forward with long term goals to develop new nanoparticle-based medicines and implantable nanosensors to help diagnose health conditions, they’re also finding ways to use nanostructures to improve medical devices that are already being used.

“Our short term solutions, which have received FDA approval, are simply taking off-the-shelf medical devices like a hip implant or a spinal implant and putting nano-features on those implants,” Webster said. “It’s the same chemistry we’ve been implanting for decades. It just has a different nano-scale roughness.”

That microscopic change in texture has a significant impact on the surrounding tissue. The bone around the implant grows faster and healthier than with traditional implants, which means the implants will work better and last longer.

Webster and his team also discovered that the change in texture cuts down on bacterial growth. Now they’re working with the Department of the Defense to see if nano-textures can help reduce bacteria and viruses on materials used for temporary shelters in war zones.

“We want to improve things,” Webster said. “We think there are much better ways that we can treat human diseases and human problems.”

This story was originally published by News@Northeastern on January 8th, 2019.