by Joshua Timmons, Biology, 2017

Sara Williams remembers her first fieldwork experience well. It was after the BP oil spill and she, and a team of students under the direction of Dr. Mark Patterson, were using an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to look for traces of oil in a Louisiana saltmarsh. “We had to walk the robot into this small lake where all of the fishermen dumped their fish heads and turkey necks,” said Williams, “I remember long, hot days with hordes of mosquitoes and dangerous thunderstorms.” While that sort of research may intimidate the average undergraduate, it hardly fazed Williams and has done nothing to deter her from her unrelenting focus on the pressing environmental questions at hand.

Of the more than 16,000 National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship applicants this year, only 2,000 were awarded. Among the promising graduate students that applied, the few picked were chosen for excellence in their area of research and their potential to continue pushing the boundaries of science’s knowledge. It’s a rare honor and represents a bright future in their field of interest. One of this year’s recipients, Sara Williams, is currently a Research Technician at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center and also an incoming graduate student in Northeastern’s Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology PhD program.

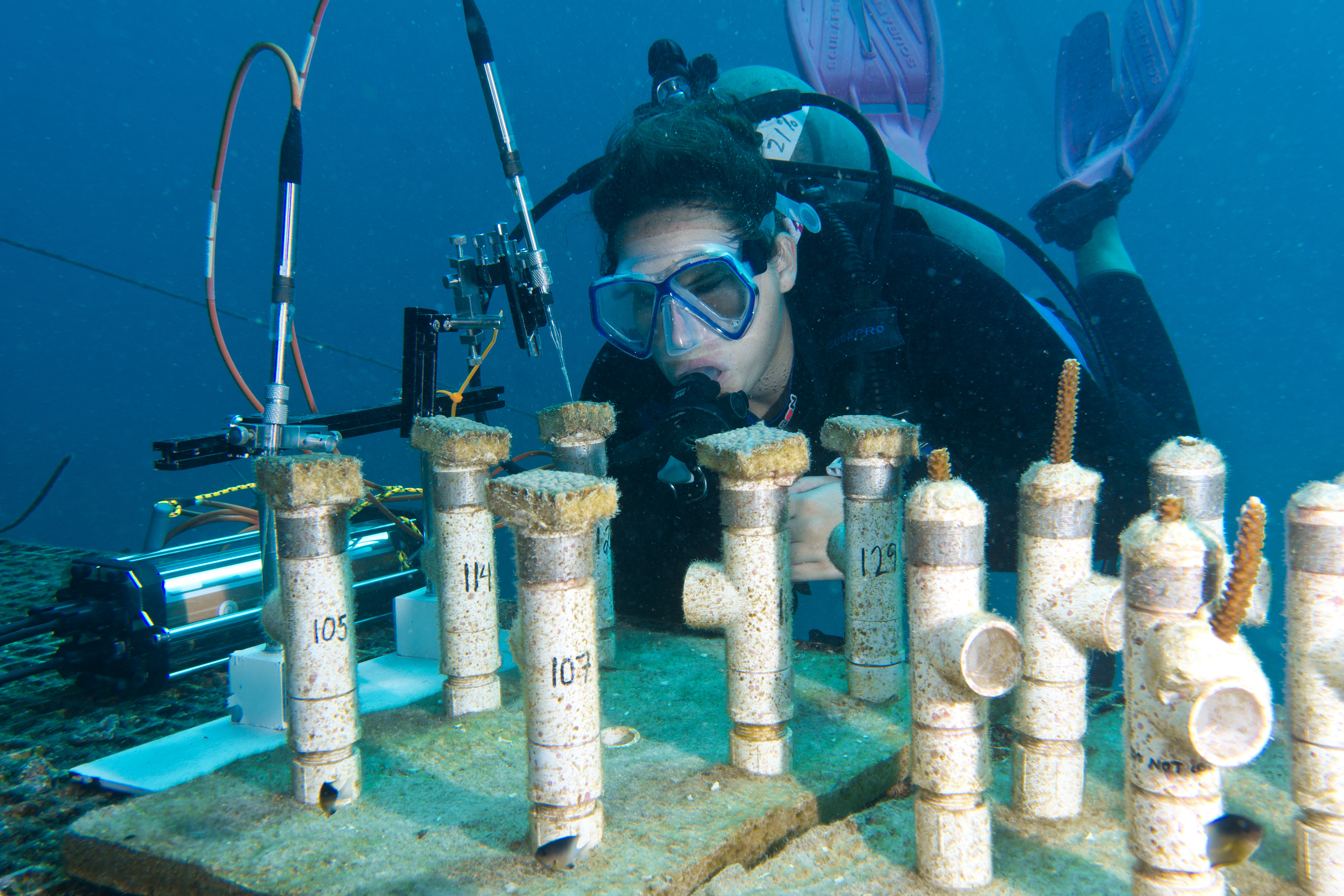

Sara Williams during a research dive.

A native of Richmond, Virginia, Williams showed an early affinity for water, getting her SCUBA diving certification at the young age of 15. Her love of the marine world continued through college at The College of William and Mary where she completed her undergraduate degree in physics with a minor in biology. For her honor’s thesis she measured the mixing time of fluids inside the digestive system of corals. Dr. Mark Patterson, Williams’ undergraduate thesis advisor and now doctoral advisor, explained, “Sara is a great example of how research begun while an undergraduate can have lasting influence on a person’s career in science. She was willing to tackle challenging measurement problems in understanding how corals work as living machines.”

Explaining the importance of coral reefs, Williams cites their use as a habitat for fisheries, rich biodiversity providing for new medical compounds, and natural barrier to storms. Unfortunately, our ability to protect these valuable resources is hindered by a lack of knowledge. “Just like how doctors need to understand how the human body works, we need to understand how corals work to see how they will respond to stress,” said Williams. Corals are colonial organisms and their individual units, polyps, are connected by an “internal plumbing system,” called the gastrovascular system. Williams appreciated the importance of understanding this system and drew upon her background in physics to design a novel method for analyzing the flow rate of fluid through these gastrovascular systems.

Williams realized that she could take advantage of the natural symbiotic algae that live inside coral tissue and produce oxygen in the presence of light. By turning off the light and then measuring the oxygen drop inside coral polyps with specialized glass microsensors inserted into the polyp’s mouth, Williams could determine the “mixing time” of fluid within the coral gastrovascular system. From that breakthrough, and continued work, Williams has created predictive models that enable researchers to measure the “connectedness” of networks of polyps. Williams has proposed to study how different types of polyp connection affect how corals share resources and respond to environmental stress; and then, by using network theory, create a “6-degrees-of-coral-polyp-separation” model. This sort of predictive analysis ties in well with another of Williams’ former projects that she undertook while working at Mote Marine Lab in Sarasota, FL as part of a NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates internship: mapping patches of coral reef to determine whether symptomatic corals were afflicted by contagious disease or eliciting an environmental response. Another long-term goal of Williams’ research is to understand and predict which coral species are most affected by environmental stress based on their level of connectivity so that irreversible damage might be mitigated.

For other students and nascent researchers, Williams had the following advice: “you have to keep asking questions and make your own opportunities; you can’t wait for people to just hand you a research project.” She cited her own experience approaching her current mentor and adviser, Dr. Patterson, during her Introduction to Marine Science class. “When I started the course, I sat in the front row every day, and after the very last class of the semester I went up and just asked if I could work in his lab,” said Williams. Explaining the appeal of Dr. Patterson’s research, Williams said that it matched closely with what she had dreamed of doing, “I knew that his lab would be the key to my combining physics, biology, and diving while at the College of William and Mary.”

Never one to miss out on an adventure, Williams took part in Fabien Cousteau’s historic Mission 31 where, on top of doing fieldwork, she Skyped with Boston’s Museum of Science from the world’s only underwater research facility, Aquarius. Sixty feet beneath the ocean surface and nine miles off the coast of Key Largo, FL, Williams was explaining the physiology of coral to viewers 1,500 miles away. “Sara has a gift for communicating science to the lay public,” said Dr. Patterson, “it has proven valuable in the efforts of the Marine Science Center to raise awareness of what we do in the area of Urban Coastal Sustainability globally.” Other examples of Williams’ ability to communicate have been through her help giving laboratory tours to Northeastern Board of Trustees, visiting congresspeople, as well as staff and donors. “She has also excelled at creating online lesson plans and other content for STEM education,” said Dr. Patterson.

Sara Williams works with the microsensors while on a dive during Mission 31. photo by Christopher Marks

Long-term, Williams sees herself in either academia or at a research institute like Mote Marine Lab. “I’d like to continue studying coral physiology and biomechanics, however, my proposed research can also be expanded to better understand other modular organisms and networks.” When it comes to the future of her research, Williams isn’t worried about reaching a roadblock. “My favorite aspect of science is that the answer to one question often creates so many more questions,” she said. Williams is hopeful that her research on networks and resource sharing in coral will lead to applications for security, transportation, and other technical networks: “Corals are just another system of links and nodes, we can learn a lot from nature’s networks and apply millions of years of evolutionary adaptations to improve upon society’s infrastructure.”

Jessica Torossian, a student in Prof. Brian Helmuth’s lab, and Robert Murphy, a students in Prof. Jonathan Grabowski’s lab, both received NSF Fellowship honorable mentions.