Dr. Marc Cohn, Ph.D. is a Professor Emeritus in seed biology at Louisiana State University, where he is still teaching his graduate level ‘professional development’ course and is business manager for the Southern Section-American Society of Plant Biologists. During his 40-year academic career, he was the recipient of numerous teaching awards from LSU, served as editor of Seed Science Research for a decade, and received the Seed Science Award from the Crop Science Society of America, the highest honor given to a seed biologist in the United States. However, to many people, he’s better known as Dr. Jazz, a radio DJ whose broadcasting ‘career’ also began on Huntington Avenue. Below, he shares some of his experiences at Northeastern and in his career as a biologist and jazz broadcaster.

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Marc Cohn.

What did you study at Northeastern?

B.A. in Biology, class of 1971

Do you have any specific memories about your time at Northeastern that stick out or are important to you?

A.K. Khudairi calling me into his office and asking me, “Well, you ask me so many questions in class. So, now I have one for you. What makes a tomato turn from green to red?” That query turned into a co-op job during my junior year in his lab working on fruit ripening. After a quarter, he asked, “Well, Mr. Cohn, what do you want to do with your life?” That conversation led to an assistantship offer at Cornell, and the rest is history. Before that, my plan was to go to med school and be a surgeon. (That’s the highly abridged version of the story.)

Charles Meszoely’s comparative anatomy lab final, in which I had to do a display dissection of the auditory ossicles of a dogfish shark (cutting an ossicle resulted in a reduced grade, as did cartilage on the membrane or breaking the membrane). I got my A. The whole class was gathered around as I removed the last bits of cartilage, without breaking that membrane. After all, these are the hands of a surgeon (who knew that they would be the hands of a seed surgeon in later life).

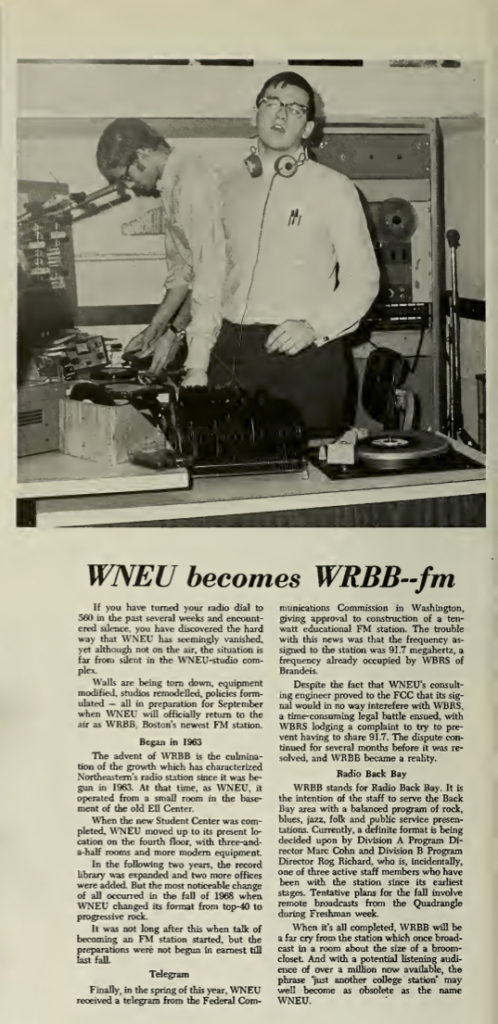

Doing a radio remote broadcast from the quad during orientation and playing an elderly neighbor’s request for Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” at 8AM – full blast on outside speakers to the surrounding neighborhood. During the student strikes in (1970), being camped out on a fire escape overlooking Hemenway Street and doing ‘play-by-play’ live reporting on WRBB of the police charge. One of our reporters got a front page mention in the New York Times for covering that incidence. Waking up in a cold sweat during finals, fearing I’d forgotten what a Grignard reagent did. My first co-op job in Food Science at M.I.T., working the overnight shift to get lipid oxidation kinetic data.

When did you first get into jazz?

Mom had a record club subscription, and I got to select the free bonus record every couple of months. The circular had a jazz section, and I was curious. Then, an FM radio arrived in the Cohn household, and I discovered ‘Just Jazz’ with Ed Beach on WRVR. Man, what a voice, and he concentrated on one artist each show. So, I studied with Mr. Beach during junior high and high school. And there were live Friday night remotes from the old Half Note with Alan Grant on WABC-FM. Remember, this is New York City. From grades 7-12, I went to school a couple of blocks from the offices of Blue Note Records and a block from the Lincoln Center Music Library. By the time I left for college, I had listened to EVERY jazz record in that library.

Tell me about your jazz broadcasting.

Then student Dr. Cohn is mentioned in this article found in the 1971 Cauldron yearbook from Northeastern Archives. Fellow broadcasters Ken May and Norm Thibeault are pictured in the studio.

We had a pirate radio station in White Hall freshman year, and the guy who ran it (Paul Diamond), while being a hardcore Top 40 DJ, thought it would be a good idea to have some jazz on. He was also on WNEU and got me into the station. Initially, I sat in on a Sunday afternoon jazz show, just bringing in albums for the DJ to play. That led to me doing my own jazz show, as well as playing blues, R&B, a bit of top 40, and general progressive music programming. I ended up as the first program director of WRBB when it went from closed circuit to citywide.

When I went on to Cornell for graduate school, I broadcast jazz every Saturday night on WVBR, as well as general programming during the week, a wildly popular Saturday afternoon soul show one summer (that’s 8 hours on the air in one day – whew), morning drive one semester, and an occasional country music show. Broadcasting the morning drive led to me being the only student in my ‘Ion Transport in Plants’ class who was fully awake. Three hours of morning ‘pop’ radio either ‘wires’ you or kills you. Ralph Obendorf at Cornell first knew I’d arrived in Ithaca because he heard me on the radio while driving around town the weekend before school started – not exactly the most studious first impression of a new Ph.D. student!

I had intentions of being a ‘serious professor’ when I arrived at LSU, but jazz radio was so bad in Baton Rouge (this would be 1978), I had to do something! I had a weekly jazz show from 1978-1995 on KLSU and its predecessors. After about a decade break to edit ‘Seed Science Research’, the premier journal in my field, I’ve come back to jazz radio on WHYR-FM, a community radio station; the show is also syndicated on the Pacifica Network, available 24/7 on mixcloud.com/drjazz, and is a featured broadcast on the website, AllAboutJazz.com.

What do you think is a song that everyone should hear before they die?

Only one? Sorry. West End Blues (Louis Armstrong), Koko (Charlie Parker), all of A Love Supreme (John Coltrane), Free For All (Art Blakey) and the Criss Cross album (Thelonious Monk).

Did your career in science affect your career in jazz or vice versa?

Absolutely – in both directions. Science at its heart is an art and a craft (often forgotten). If you think of biology as simply putting an organism through the ‘technique du jour’, you’ve missed the point entirely.

In Science, you learn the fundamentals and dogma of your field, but then you have to ‘listen’ to what the organism is telling you through the data and proceed accordingly. (The organism doesn’t care what you think – it does what it does, and your job is to figure that out.) Music is also both an art and a craft. Imagination and creativity are at the core of both. I learned how to talk, excite and reach people in radio, and those skills are essential for good teaching. I also learned how to cope with dealing with people because of radio.

What is your favorite part of being a professor?

Everything about doing actual research and teaching, except (1) the administrative busy work, (2) the constant administrative push to put out papers (we’re not on an assembly line putting cars together!), and (3) excessive pressure to write grants (when you don’t need the money and have as many students as you can handle properly). Mentoring Ph.D. students is a challenge and a thrill (when you see the ‘light go on in their heads.)

What is your favorite part of being a broadcaster?

Everything but the paperwork. It’s particularly stimulating (and sometimes nerve wracking) to look at that blank 2-hour canvas at the start of each week with the entire history of jazz at your disposal. Then, how do I figure out how to make the listening experience out of the ordinary, yet informative, for the listener? It’s kind of like science, just because you can do an experiment (because you know a technique) doesn’t mean it’s the best experiment to do. So, just because I can play 2 hours of tenor saxophone quartet tracks every week doesn’t mean that I should (and by the way, I don’t).

Summing up?

Well, it’s been a good, fulfilling ride. Growing up in New York City was a precious. My time at Northeastern was critically important for development of the rest of my life. Culturally, Boston was fantastic. Northeastern Co-op was absolutely essential. I was much less than a model college student and probably would not have graduated without the breaks provided by the work experience in biological research. I really “found myself’” through Co-op (and radio too)! While Baton Rouge was not on my career map, I’ve been able to construct a contented life here with a few local friendships and colleagues world-wide in both my avocations, which I plan to pursue as long as I wake up every day.